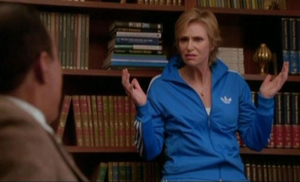

Source: ZackTaylor.caIt’s hard to imagine Jane Lynch in any form other than the one that currently graces our TVs every Tuesday night, or that the 6 ft., pixie-cut comedy queen didn’t simply spring into being as she is, making whichever stork lucky enough to have her as its load work for its money (and probably laugh its tail off).

Source: ZackTaylor.caIt’s hard to imagine Jane Lynch in any form other than the one that currently graces our TVs every Tuesday night, or that the 6 ft., pixie-cut comedy queen didn’t simply spring into being as she is, making whichever stork lucky enough to have her as its load work for its money (and probably laugh its tail off).And that’s the thing about Lynch: her persona is so concrete, so undeniably hilarious and memorable that any imagining of an actual young and permed version is moot.

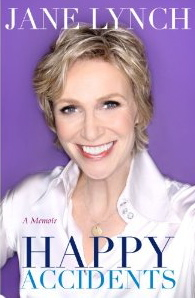

So imagine my surprise when I started to turn the pages in her memoir, Happy Accidents, and found a voice that is completely different from the one that spews out of Sue Sylvester and the various laugh-inducing straight-faced characters she’s played in movies like Best in Show, For Your Consideration, and The 40-Year-Old Virgin.

So imagine my surprise when I started to turn the pages in her memoir, Happy Accidents, and found a voice that is completely different from the one that spews out of Sue Sylvester and the various laugh-inducing straight-faced characters she’s played in movies like Best in Show, For Your Consideration, and The 40-Year-Old Virgin.

The dedication page alone is enough to set the following 302 pages off to an unexpected beat:

“For Mom and Dad … and every kid out there mustering up the courage to answer the call of their own hero’s journey.”

So this isn’t just going to be a 300-page romp about tallness issues and/or the genius of her comedy chops? I wondered.

As it turns out, there’s more to Jane Lynch than socks the funny bone on a regular basis. She isn’t concerned with peppering each paragraph with quotables or wowing her audience with the blunt humor we love her for.

Instead, there’s a sincere earnestness, the feeling that she had been bottling up these stories of family and self-loathing and growth until she couldn’t anymore and finally let them bubble over and explode into a book.

“As much as I joked around, and as loving as my parents were, I still always felt a weird, dark energy bottled up inside. My body was filled with a buzzing nervous tension that constantly threatened to erupt in what my mother came to call ‘thrashing’ (14).” Source: PacSignatures.com

Source: PacSignatures.com

She’s to the point, simultaneously straightforward and vulnerable, walking the reader through a lifetime of woes and regrets with a 20/20 hindsight that says, “Yeah, I was a crappy person when I was younger, but I’m better now, and you can be, too,” rather than, “I have a deep, dark soul no one understands, but I wrote this anyway because my agent told me to and I like to impress people with my depth and darkness.”

Indeed, the experiences she shares in the first half or so of the memoir don’t paint her as the idealized comedienne we see today. From tormenting her sister for no reason at all to becoming a loudmouthed, whiny diva in her college theatre department, to being a quitter and cast-off and alcoholic in her post-grad years — these are all a stark contrast to the Jane Lynch we know.

She invites you to despise that younger, naïve person who shared her name, but also manages to draw sympathy and understanding, as the older and wiser JL finally understands the origins of The Angry Lady, herself.

Both her hunger for admiration and her struggle with queerness — which are arguably tied — play central roles in her story, though maybe it’s because I experienced closetedness, myself, not too long ago, but it resonates. And I’d imagine that even straight readers can understand that constant fear of rejection, of inner-turmoil over identity and budding adulthood; and, judging by the way Lynch contextualizes everything and tells her story in an honest and relatable way, she agrees. Her story isn’t just about lesbianism, it’s about accepting every facet of yourself and doing your best to take the chances necessary to be happy. To do things for the sake of happiness.

“Back in Dolton, when I was writing letters to Hollywood agents, my main objective was to be adored, fawned over … Had I become famous as a younger person, it might have been a disaster for my insecure self. I would have been swayed by the public’s opinion … and my sense of self-worth would have been at their mercy … But once I’d reached my thirties, I just wanted to work…

“And that seemed to be how my romantic relationships were going, when they were happening at all. After all the drama of coming out … my sex life lay fairly dormant. I was just starting to be good at friendship. I was really taking my time with the intimacy thing (145).”

Suddenly, the dedication page makes sense: Happy Accidents is a cautionary tale, but one with a happy ending. One so sincerely and earnestly told that throughout reading I often imagined Lynch standing centre-gym at some cheesy, but still effective, middle school DARE assembly, as that cool PE teacher whom kids actually listen to because she “keeps it real.”

“I would love to be able to go back and tell that young girl sitting at the dining room table in Dolton, Illinois … to trust herself in the world. I’d tell her, ‘You don’t have to drink, and you don’t have to be anxious. You just have to be you, and everything will be fine.’

“I would never presume to give anyone advice on how to walk their own path, as I have no desire to deprive anyone of their unique journey; as you can see, my own has been customized to fit my needs and my particular brand of humanness. But I will offer this in the way of counsel: find what it is you do best and do your best with it (302).”

The call of her journey, then — because I’m counting her as a hero now — is to be unafraid of change and of taking chances, of finding something you’re passionate about and sticking with it til the end.

So while the book doesn’t comprise essays of flat-out hilarity, like most comedienne-written memoirs do these days, it still serves as great insight into the past of a once mysterious Jane Lynch and, maybe even a little bit, that part of yourself that still has doubts.