We’ve all heard of Alternate History, a genre of historical studies that discusses various permutations of “what if” scenarios. For example: What if Hitler won WWII; what if the North fell to the South; or what if the Galactic Empire defeated the Rebel Alliance? How would our world be different today?

Fortunately for the sweater-vested literary theorist in all of us, this endlessly amusing cerebral exercise can be extended to the realm of literature! What if Lewis Carroll had written The Divine Comedy; what if Ernest Hemingway had drafted Romeo and Juliet; or, what if Oscar Wilde had penned The Hobbit?

Here is a chapter taken from best-known Alternate Lit textbook, Alternate Authors: The Higgledy-Piggledy World of Re-Imagined Wordsmiths, published by Harcourt B. Jovanovich in 1958. Grab your snazziest reading glasses, a cup of piping hot Earl Grey (or a flagon of schnapps) and prepare to get mindf*cked by the written word.

The Divine Comedy by Lewis Carroll

This passage is excerpted from Carroll’s Canto III of The Inferno, a description of the inscription above the gate leading into Hell:

Through me, enter, and topple down this rabbit’s hole,

To the doleful city! Beware your slithy soul!

For you’ll find tortured hatters, forsaken dormice, a grief-stricken hare,

Suffering curiouser and curiouser punishments fair!

So beamish wanderer, the last counsel I’ll say,

Is ‘Abandon all hope! Callooh! Callay!’

Notice how Carroll captures the essence of misery while imbuing the gate’s inscription with an air of whimsy. Perhaps the dissonance created by pairing whimsy with suffering is metaphorical for Dante’s own emotions as he approaches Hell’s ingress: curiosity and fear.

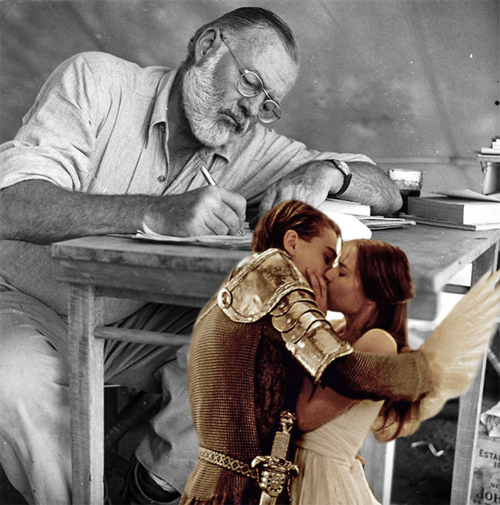

Romeo and Juliet by Ernest Hemingway

An excerpt from the first page of the text:

The wind came from the East and Romeo was sitting on a stoop and he was upset about what had happened with Rosaline. He thought he’d never feel happy again but that wasn’t the case, as time would soon tell. He would first feel happy and then he would feel sad and then he would feel dead. The wind changed directions and Romeo stared at the horizon. In nearby Verona a girl named Juliet also stared at the blue cloudless sky.

Through lean, indifferent prose, Hemingway describes the protagonist’s psychological status quo at the inception of the tragedy. The wind becomes a tenuous metaphor for Romeo’s fate.

The Hobbit by Oscar Wilde

This is the opening scene of Wilde’s The Hobbit, wherein Gandalf arrives at Bilbo’s home on a mission.

The drawing room of Bilbo’s hobbithole. The room is homey, if a bit cluttered. The sound of lute and fiddle music is heard in the adjoining room. Bilbo eats mushrooms and bacon as he taps his foot to the music. Gandalf ENTERS.

BILBO

How are you, my dear Gandalf? What brings you up to the shire?

GANDALF

Oh, a quest, a quest. What else should bring one anywhere? Eating as usual, I see, Bilby!

BILBO

I believe it is customary in good society to take second breakfast at eleven o’clock. Where have you been since last Thursday?

GANDALF

In Rivendell.

BILBO

What on Middle-earth do you do there?

GANDALF

When one is in the Shire, one amuses hobbits. When one is in Rivendell, one amuses oneself. Elves are excessively boring.

Wilde’s Hobbit offers true subversive social commentary on fin de siècle London. Gandalf’s suggestion of a quest is clearly a satirized paradigm of beau monde materialism. There you have it, bibliophiles. Now, let’s see your three thousand word essay on the sexuality of rhymes in Dr. Seuss’ Lolita!

Photoshoppin’ by Erika Cervantes